Black Wednesday

16th September 1992 - Black Wednesday - what a day that was.

The sun was glorious. I was on a beach in Italy soaking up the sun when news began to filter through that something called the ERM was causing interest rates to rise in the UK.

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism was being used by governments in the run up to a single currency. It meant little to me at the time, but, the sudden rising interest rates meant a lot. My mortgage doubled in cost that day and I wouldn't be able to afford to pay it when I got home.

I remember watching Norman Lamont, the Chancellor, on the news, standing outside The Treasury declaring that the UK was to leave the ERM. I didn’t pay much attention to the man standing behind him in the background. Why should I?

The Bank of England later calculated that Black Wednesday cost the UK £3.4 billion. It deepened the recession that the country was already in and some homes, including mine, halved in value.

That day changed many things. The shape and future of British policing was one of the things that changed forever too.

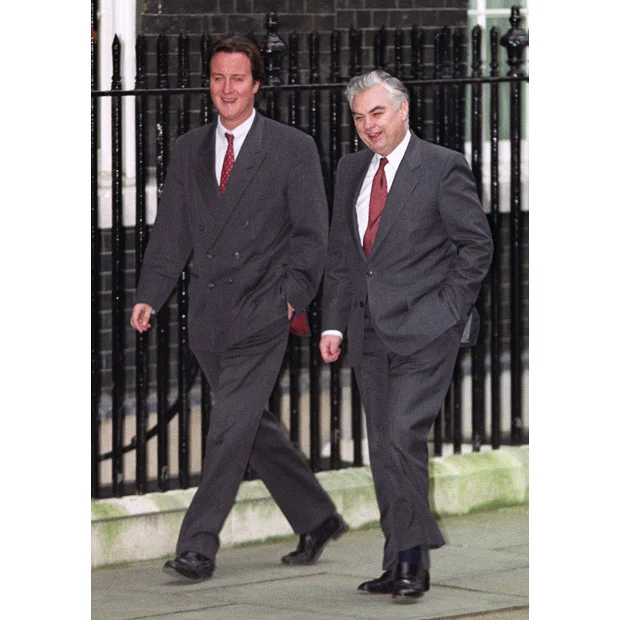

The man in the blue suit, the one stood behind Norman Lamont outside the Treasury, was David Cameron.

Cameron had been Lamont’s special advisor for some time and was looked upon favourably within political circles of Westminster, at least he was until Black Wednesday. When Lamont was sacked in May 1993 for the ERM debacle, Cameron found himself at the mercy of the new Chancellor, Ken Clarke, who swiftly gave him his marching orders, told him to clear his desk and to leave Westminster.

And that should have been that...

But, something changed. Later that day Ken changed his mind and he softened his approach to the young Cameron. Somehow, someone found Cameron a job as an advisor with the Home Secretary, Michael Howard.

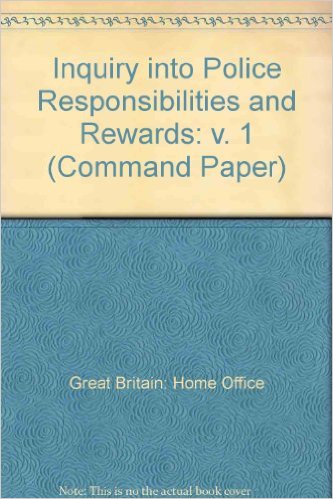

In June 1993, a month after Cameron had arrived at the Home Office as Howard’s advisor, a report written by a certain Sir Patrick Sheehy was to land on Cameron's desk. The report, oddly enough, had been commissioned the year before by Ken Clarke. The Sheehy report, as it became to be known, was to be a way for Cameron to prove himself again. Prove himself to his peers and - more importantly - to prove himself to Ken Clarke, the man who had commissioned the report in the first place, and, the man who had allowed him to stay in Westminster.

The Sheehy report was about Policing, its remit: “to examine the rank structure, remuneration, and conditions of service of the police service of England and Wales, in Scotland and in Northern Ireland, and to present recommendations if found necessary.”

The report was aggressively seized upon by a power hungry Cameron who set himself, and the Home Office, on a collision course with the Police Federation and police services throughout the UK by trying to force through its recommendations. The recommendations were basically a series of cost cutting exercises to allowances and officers’ conditions of service. It was berated from the top down for being nothing but.

Sheehy went further than cutting allowances though. He wanted to tackle what he called the ‘jobs for life culture’ in the police. He advocated fixed term contracts for all officers, the abolition of three ranks to create a slimmer management structure, performance bonuses of up to 30 per cent for chief constables and tighter restrictions on medical retirements.

Perhaps the most controversial recommendation was the abolition of an indexed linked annual pay award. This was to be skills based and there would be no automatic right to an annual upgrading of pay in line with inflation.

That sounds familiar, I hear you say.

The vast majority of Sheehy’s recommendations were ignored and then rejected by Michael Howard, I’m sure, much to the annoyance of a power hungry David Cameron. Why do I say that?

The Conservatives lost the general election to Labour in 1997. Much of the public disquiet was about Black Wednesday and what followed. Cameron found himself out of a job. The police had won, they’d outlived Cameron and Sheehy...or had they?

Fast forward to 11th May 2010.

David Cameron stood before the country, now its Prime Minister, having agreed a deal with the Liberal Democrats after failing to secure enough votes to win outright.

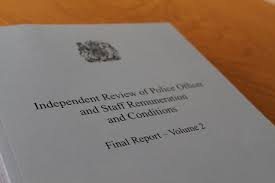

Cameron wasted no time. He instructed the Home Secretary to review police pay and conditions and a former rail regulator, Tom Winsor, was given the job of Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabularies, a role that had previously always been held by a former chief police officer.

Winsor promptly produced a report, which, as you can guess, looked rather like the one that Cameron tried to force through between 1993 and 1995. Winsor's report is now being enacted by a very aggressive government.

I am a former police officer, and perhaps, a little biased when looking at this. The police are not a perfect organisation and there were and are many things that could be improved to make the organisation better and more effective.

Attacking people's pay and working conditions does not make them work harder. It doesn't make them become more effective. Creating job uncertainty doesn't make people feel valued, nor make them want to work harder either - it demoralises people and destroys their confidence.

The Conservatives claim that the police need to shoulder their ‘fair share’ of the country's debt following the banking crises. However, I wonder how much of this is a personal crusade for things that were said and done in the 1990s. An ambitious David Cameron who failed? A vindictive man determined to get his own back?I don’t know the answer - you decide.

All I know is that, all this, started one Black Wednesday while I was sat in the sun on the beach.

David Videcette is a former Scotland Yard detective and author of the hit thriller The Theseus Paradox, based on real events - available now on Amazon in paperback or for Kindle. Sales support the charity, the Police Dependants' Trust to help officers who've faced tragic events on duty.

“I can’t tell you the truth, but I can tell you a story...”